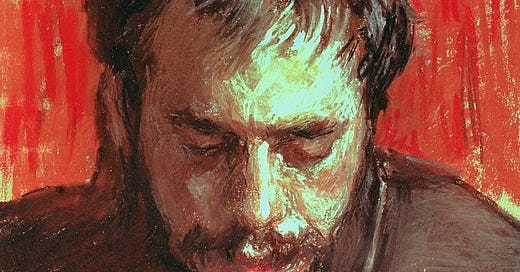

Demons by Fyodor Dostoevsky (Penguin Classics, translated by Robert Maguire)

It is a strange feeling to be writing about Demons on the day Trump leaves office. It was equally as strange to read the novel over the last couple weeks, which included a white nationalist riot at the Capitol. But I’m not about to spend my time making a bunch of overly simplistic comparisons of the chaotic events of Dostoevsky’s novel to the mess of current American politics. There is already an article that does exactly that. If you read classics, 19th century Russian and French classics lately for me, there’s an entire career in comparing and contrasting the cycle of political unheaval.

Dostoevsky is too complex of a writer to pigeonhole his works with any one interpretation or theory, with that said there is no denying how alarmingly relevant Demons’ narrative of ideological dissolution is. Russia in the late 1860s saw a surge of student groups heavily influenced by socialist and revolutionary ideas that were spread through pamphlets. Dostoevsky came up with the idea of a “pamphlet novel” where he would focus on a group of violent pseudo-revolutionaries inspired by Sergey Nechayev and his group who ended up murdering one of their own members. At the time he begun working on the “pamphlet novel” he was also working on a philosophical novel titled “The Life of a Great Sinner” which explored the moral consequences of atheism. Both of these projects ended up being combined as one.

Demons is the “chronicle” of a young man recounting the strange happenings in a provincial town. The narrator remains at the periphery of the novel, acting as a detached and rather snobbish observer. He is part of an informal intellectual club hosted by Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky, who was a short-lived professor, half-hearted tutor, and at the time of the story is a full-time intellectual rambler. For the past twenty years he has been part of Varvara Petrovna Stavrogina’s household, a very small part of this time spent as Varvara Petrovna’s son’s tutor. The first section of the novel focuses on Stepan Trofimovich, his youthful ambitions, tragic marriages, and eventual complaisance as a comical local legend. Like many of the younger men he associates with, he spent much of his early adulthood abroad and as a result is well-informed in the various intellectual developments of Europe in the 19th century. The most lasting impact of his international excursions is an incessant peppering of French in his speeches. A fascination with Western cultural developments is what connects Stepan Trofimovich’s gloomy gang, with their host using the meetings as a means to stand on a pedestal bemoaning the stagnation of Russia is contrast France and Germany.

The first big development that begins the series of ominous events to strike the town is the return of two sons. First is the arrival of Nikolai Vsevolodovich Stavrogin, Varvara Petrovna’s son and Stepan Trofimovich’s former tutee. A pale, elegant, taciturn young man, Stavrogin returns shrouded in a cloud of mystery. Reports from Petersburg have brought news of Stavrogin’s great social success, but also debauchery and duels. Two scandals occur in town involving Stavrogin that seem to confirm the darker suspicions regarding his character, but the controversy somewhat settles as it is revealed he suffers from strange health issues (inspired by Dostoevsky’s epilepsy).

The next son to return is Stepan Trofimovich’s, Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky. Unlike Stavrogin, who is doted on and adored by his mother, the relationship between Stepan Trofimovich and Pyotr Stepanovich is more strained. Pyotr Stepanovich’s mother was Stepan Trofimovich’s first wife, and after her death he was raised by relatives with no involvement from his father. He returns to retrieve money owned to him by his father, but remains to hover around Stavrogin, who he has a mysterious past with, and also to insert himself into the town’s society. He particularly attaches himself to Julia Mikhaylovna von Lembke, the wife of the recently arrived Governor. Julia is a passionate social climber and hosts her own intellectual salon where she embraces the youth, even the most radical in order to “save them”. Pyotr Stepanovich becomes her most prized adviser, much to the unhappiness of her jealous husband.

It is Stavrogin and Pyotr Stepanovich and their strangely magnetic presences that is the central focus of the novel. Stavrogin, with his sickly beauty, elegance and mysterious past, fascinates everyone. When he is around all eyes are on him. On the other hand, Pyotr Stepanovich is a shadowy figure, seemingly known by all and with influence over many, but always remaining transitory. Both characters carry ominous suspicion wherever they go, Stavrogin’s of a tortured and haunted quality while Pyotr Stepanovich’s is of a more ominous and calculated nature. But their natures ultimately are closely and inevitably linked.

Stavrogin is a man of all-consuming detachment, his affections and friendships only exist in the moment and are forgotten as soon as he is alone. When he stays with his mother he remains shut in his room and schedules the times when he will accept visits, and is endlessly breaking engagements without any explanation and being unaccounted for during key moments. His strained romance with Lizaveta Nikolaevna Tushina, the beautiful and refined daughter of a social rival of Varvara Petrovna, is source of much attention early in the book, but gradually and painfully loses force as the wreckage of Stavrogin’s past continues to be revealed.

As the rumors of a secret group of agitators spread, it’s impossible to ignore the implication that mysterious, secretive Stavrogin is involved. But his emotional emptiness is too gaping even for cold ideology. The revelation of his relationship with Marya Timofeevna Lebyadkina, the lame and mentally challenged sister of drunken Captain Lebyadkin, hints at an underlying morality and dignity, but even this proves to be a soulless affair.

At this point I must mention the censored chapter “At Tikhon’s”. Mikhail Katkov, editor of The Russian Messenger which serialized Demons, refused to publish the chapter. Dostoevsky considered it essential to understanding Stavrogin’s character, but was unable to convince Katkov. This is unfortunate as Dostoevsky is absolutely correct, the chapter sheds vital light on Stavrogin’s strange and unpredictable actions. To be fair, it is deeply disturbing. Stavrogin’s confesses a horrifying crime to the monk Tikhon. In the confession, he reveals the truth of his moral detachment that is obscured throughout the rest of the book by his silence. Behavior to him is a social experiment, a way to try out morality and immorality, belief and nonbelief, like interchangeable masks depending on the situation and as a means to observe the consequences they have on others. His relationship with Marya Timofeevna, as well as his past affair with Ivan Pavlovich Shatov’s sister, Darya Pavlovna, prove to be a direct result of this behavior. Without this chapter Stavrogin’s fate, while appropriately grim, is mere shock value with no real purpose or resolution. Dostoevsky understood the importance of reckoning with the deep-rooted cruelty at the heart of Stavrogin’s indifference.

The opening of Part III marks the moment when all the tension and intrigue erupts into a series of manic and violent events. The scene is Julia Mikhaylovna’s much-anticipated gala which is supposed to solidify her social and intellectual influence. However, inept planning, snobbery, political tensions, and, to cap it all off, antagonistic ruffians who are snuck in, combine to detonate long-simmering tensions. And when at the moment of peak volatility a nearby town is set ablaze followed by the discovery of a gruesome murder scene, the cryptic machinations of Pyotr Stepanovich come into focus.

Pyotr Stepanovich is a nihilist, a member of a secretive society with the goal of assembling five-person groups around the country to systematically sow chaos and unrest and to ultimately assume power when all traditional institutions have collapsed. He says this himself to Stavrogin in a rare moment of explanation and forthrightness. Usually when talking to the members of his group he speaks in the tone of a formal representative of “the organization.” Is there a large-scale organization? Or is he a lone manipulator pulling the strings of his followers to commit acts of arson and violence? Fittingly these questions are never resolved, and it is this uncertainty of the level of his power and importance that makes him so effective.

What has remained the most relevant aspect of Demons is its depiction of extremism. The plottings of Pyotr Stepanovich and the consequences of an orchestrated atmosphere of instability and chaos has echoes everywhere you turn in the roughly 150 years since its publication. Sergey Nechayev, the model for Pyotr Stepanovich, has been called “a Bolshevik before the Bolsheviks” and the strain of extremism he represented which sees progress only in the aftermath of widespread collapse has never stopped seeing new variations. Dostoevsky depicts Pyotr Stepanovich as a gifted manipulator, a man able to exploit people’s vanities and values for his own gain, but also a magnet for weak and unstable personalities. His minions are bumbling fools and cowards, showing in full force during the climactic murder scene. Dostoevsky’s disdainful portrayal of political extremism as a haven for ignorant reactionaries, embittered social outcasts, and the mentally unstable has remained terribly true.

But political extremism isn’t the only form of extremism Dostoevsky’s explores. With Ivan Pavlovich Shatov and Alexei Nilych Kirillov he turns his eye on religious extremism. Kirillov has lost his faith, but in its place has developed a radicalized version of self-will. If God does not exist, then all that exists is self-will. He believes true freedom comes from the ultimate act of self-will—suicide. But further emphasizing the lengths of his fanaticism is the fact the he believes by killing himself he will become God because God is self-will, and by killing himself simply because he chooses to will reveal this truth to the entire world. Shatov has gone the opposite direction—while previously being an atheist and supporter of revolutionary socialism he has now committed to traditional Christian heritage. Shatov was once a minor member of “the organization” but now equally rejects their ideology as well as the lazily open-minded belief buffet of Stepan Trofimovich’s meetings. As a result he is an outsider to all and the suspicion this causes has tragic consequences.

Pyotr Stepanovich represents political extremism taken to its most destructive extremes, while Stavrogin represents anti-religious extremism taken to its most immorally grotesque extremes. But as much as Dostoevsky loves to linger on shock and scandal, he is also a master at analyzing extreme personalities with amazing nuance.

Dostoevsky is a challenging writer to write about because along with his books having a massive amount of characters and narrative strands, especially his large-scale masterpieces, he also fills his works with such a staggering amount of cultural and philosophical ideas. It feels impossible to write about a book like Demons without lots of plot and character context which I normally try to keep to a minimum, and still I could have gone into so much more detail.

I would like to emphasize that in spite of all the violence, conspiracies and scandal, Demons is a remarkably entertaining and often very funny novel. The first section following Stepan Trofimovich is deemed a society novel in Robert L. Belknap’s introduction to my Penguin Classics edition, and I think that’s a perfect distinction. It often reads like a comedy of manners written in a perfectly fitting ironic tone. And this tone returns at the end when the focus returns toStepan Trofimovich, and his sad fate is all the more touching as he remains a tragic buffoon till the end.

Dostoevsky’s love for scandal and melodrama is accompanied by an equal passion for gossip, and he finds his perfect outlet in Semyon Yegorovich Karmazinov. Karmazinov is a not-even-remotely disguised caricature of Ivan Turgenev. The story of Dostoevsky’s rivalry with Turgenev has been the subject of enough essays and scholarly pieces, but I will say that the Penguin Classics edition comes with some fantastically malicious notes explaining the context behind the book’s many jabs at Turgenev. Like Turgenev, Karmazinov is an acclaimed Russian writer that has decided to live permanently abroad due to their disillusionment with Russian culture. This is framed as cowardice, a weak-willed escape from a Russia in rapid transition, especially when at the same time they suck up to the intellectually-minded youth in order to cling to relevance. Karmazinov reads at Julia Mikhaylovna’s gala, a pompous piece that is supposedly his farewell to writing, and its barrage of mythical allusions is met with mockery from both the low-class “rabble” and the society people. A moment of cruel and hugely amusing mirth before the eruption of violence and betrayal.

Demons is an incredible piece of work, and a major improvement over Dostoevsky’s previous novel, The Idiot. The latter’s Prince Myshkin is a passive and mysterious figure like Stavrogin, but his character is used as a blank soundboard for the revolving door of characters and their dramas surrounding him. The book progresses with and endless cycle of gatherings where most of the major characters find themselves together and they take turns going on exhaustingly long monologues. The only instance of most of the major characters arriving in a room together in Demons doesn’t happen until 200 pages in, a moment that signals the return of both Stavrogin and Pyotr Stepanovich. Stavrogin often has characters tracking him down to talk at him, but he is a master of escaping interactions as well as consequences. Dostoevsky seems to realize that his highly convoluted plotting tendencies and fascination with dramatic monologues are not suited to follow a single perspective for 600-plus pages. Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment is the vessel of his own demise enough to carry an entire lengthy novel, but Demons with its inventive use of a passive and potentially complicit narrator (think of the ways he says “our people” when talking about Pyotr Stepanovich and “the organization”) gives Dostoevsky the freedom to explore various perspectives and an exhilarating variety of ideas which makes Demons so endlessly rewarding.

Further Listening

This episode of Demons by Feeling Bookish Podcast is excellent and covers an even wider range of details and context than I have.

Well done analysis. This clip from the film is a strong piece. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrtjttyAPjo